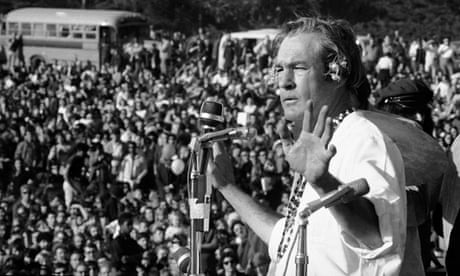

The hippie dropout movement, for all its manifold eccentricities and excesses, was conceived in the same spirit. During the Summer of Love in 1967, 30,000 turned up to a Human Be-In in San Francisco, conceived as a consciousness-raising exercise in ecstatic purposelessness. It was perhaps a bit over the top. But it is surely true that moments of indolent contemplation can provide some of life’s greatest joys. Good luck to the eventual recipients of Mr Von Borries’s “idleness grants”. They must be careful not to work too hard.

For those similarly disposed in these troubled times, a remarkable opportunity has presented itself. The University of Fine Arts in Hamburg is offering scholarship places to students committed to exploring and developing the concept of “active inactivity” or, put more simply, doing nothing. Applicants for the €1,600 grant have been set four questions to answer: What do you not want to do? For how long do you not want to do it? Why is it important not to do this thing in particular? And finally, cutting to the chase, why are you the right person not to do it? The deadline for applications is in two weeks’ time. The stoics and epicureans of ancient Greece would have agreed. Influenced by cultures of the east, thinkers such as Pyrrho in the fourth century BC used the notion of ataraxia to convey the value of serene, unperturbed tranquillity. The later Christian tradition of contemplation contained a similar insight, albeit with important caveats. The so-called Quietists of the late 17th century, accused of prioritising passivity over pious action, were investigated as heretics.

There is a temptation to greet this news with a wry smile and move on. But the recent explosion of interest in mindfulness and happiness studies suggests that Mr Von Borries’s social experiment deserves better. We live in an era obsessed with measuring, ranking and quantifying activity. Professional lives are dominated by impact assessments, league tables, targets and audits. Away from work, the tyrannical hold exerted by social media confronts us daily with the busyness of others, curated for public consumption. There is not a high premium placed on, as TS Eliot put it in Four Quartets, learning to “sit still”. Mr Von Borries’s implicit challenge is that “inconsequential” is not a synonym for “unimportant”. Doing nothing, properly understood, can be an enriching way of experiencing the world without needing to extract something from it or do something to it.

Ever since Max Weber spotted the role of the protestant work ethic in inspiring modern capitalism, there have been rebellions against the idea that a useful life is necessarily a busy one. Take the libertarian Marxist Herbert Marcuse, who in the 1960s denounced an America he saw as run by mediocre managers and technocrats. The relentless focus on productivity, said Marcuse, was producing generations of unhappy, one-dimensional human beings. “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” was the response of the 1960s counterculture.

The project is being overseen by the leading architect and design theorist Friedrich von Borries. It will be accompanied by an exhibition entitled The School of Inconsequentiality: Towards a Better Life. The scholars, having chosen their area of inactivity, will deliver an “experience report” in January.