This is a quote from a participant in a study I ran with Tania Lombrozo. If you were in our study, you read an explanation, and then explained what you had read to another participant. Each explanation was passed between 8 people, forming a single chain. The quote above is from the 8th and last person. Here’s the very first explanation in the same chain, which we took from a college-level textbook:

Tania and I were using this method for a third purpose: we’re interested in the epistemic benefits of different types of explanation. In particular, “experiential” explanations, which have a narrative structure like the example from our study at the beginning, and “abstractive” explanations, which have a structure more familiar to philosophers: relating particulars to regularities, generalizations or laws. For us, iterated learning was a way to test our prediction that experiential explanations have an epistemic advantage over abstractive explanations when it comes to transmission. (The data so far suggests we were wrong – both types were transmitted with similar fidelity!)

As Sara nicely puts it, iterated learning experiments can be seen as controlled “analog simulations” whereby chains of transmission from person to person in the lab are used to elucidate otherwise elusive cognitive phenomena. Of course, we learn from simulations and other representational stand-ins to the extent that they mirror relevant structure in the systems or scenarios of interest. The piece here highlights several potentially relevant sources of discrepancy: time (duration of the process), scale (number of individuals involved), and issues of broader context (e.g., the fact that communication is often bi-directional) all threaten validity of inferences from experiment to target. Perhaps the most critical assumption to interrogate in general is that the experimental task adequately reflect the task under study. This matter is front and center in much of the previous literature on iterated learning. Some of the cited work on language evolution hypothesizes, for instance, that iterative assignment of labels to shapes bears suitable similarity to more general patterns of language learning and imitation. To some degree (tempered in the ways Sara articulates) the natural-language-like phenomena revealed in these experiments lend support to such hypotheses.

Iterated Learning

Sara Aronowitz

_________

As Sara nicely puts it, iterated learning experiments can be seen as controlled “analog simulations” whereby chains of transmission from person to person in the lab are used to elucidate otherwise elusive cognitive phenomena. Of course, we learn from simulations and other representational stand-ins to the extent that they mirror relevant structure in the systems or scenarios of interest. The piece here highlights several potentially relevant sources of discrepancy: time (duration of the process), scale (number of individuals involved), and issues of broader context (e.g., the fact that communication is often bi-directional) all threaten validity of inferences from experiment to target. Perhaps the most critical assumption to interrogate in general is that the experimental task adequately reflect the task under study. This matter is front and center in much of the previous literature on iterated learning. Some of the cited work on language evolution hypothesizes, for instance, that iterative assignment of labels to shapes bears suitable similarity to more general patterns of language learning and imitation. To some degree (tempered in the ways Sara articulates) the natural-language-like phenomena revealed in these experiments lend support to such hypotheses.

Commentary

Thomas Icard

_________A substantial shift! But you can see how, slowly leached of all content, this fairly informative explanation about localization became a motivational quote. This technique where each person is given an input generated as output by a previous participant doing the same task is called “iterated learning”. I picked it for this post because iterated learning is used in some very interesting ways, and somewhat uniquely, is both a study paradigm and a kind of model or simulation of a further system.

Thanks so much to Sara for the fascinating work on these topics and for the thought-provoking piece here. I would like to pick up on just one of the many rich themes raised in the post, namely what we might hope or expect to learn from iterated learning experiments on explanation in particular.

Imagine you have to describe to worried school officials the fire that broke out in your room when your roommate tried cooking shish kebabs in the fireplace. You explain that your dorm is at 6400 College Avenue, a street that runs in the left-right direction on a map of your town; you are on the fifth floor, which tells where you are in the up-down direction; and you are the sixth room back from the elevator, which tells where you are in the forward-backward direction. Then you explain that the fire broke out at 6:23 p.m. (but was soon brought under control), which specifies the event in time.

Kirby, S., Cornish, H., & Smith, K. (2008). Cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory: An experimental approach to the origins of structure in human language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(31), 10681-10686.

It’s important to experience life and to describe things in four dimensions, not just two or three; that is, you need to cover all of the angles and explore all of the possibilities, and leave your mind open to new possibilities!

Aronowitz, S., Lewry, C., & Lombrozo, T. (ms). Experiential Explanations in Iterated Learning.

In other words, even if more experiential explanations are associated with epistemic benefits in ordinary conversational contexts, those benefits may be eclipsed by the many benefits of abstraction in this relatively impersonal context. What would we expect to happen in a chain of individuals, each of whom is well acquainted with the next? And what if the first person in the chain were (known by all) to generate their own explanation for a given situation? How strongly would the drive toward abstractions and generalities persist?

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Langlois et al. (2021) use iterated learning in a different context. They had strings of participants observe and recall visual stimuli by locating a point in an image. Each participant was shown the image with the point placed by the previous person, and then had to recall where the point was. By the end of the chains, they observed, essentially, a drift toward critical sections of the image: in an image of a triangle, the point moved toward the vertices, whereas in an image of a face, the point moved towards the eyes, nose and mouth. The authors argue that this reveals features of encoding in memory: because each link in the interpersonal chain shifts the point as a function of memory-induced noise, the whole chain magnifies a bias present even in a single individual, merely functioning to make it visible.References

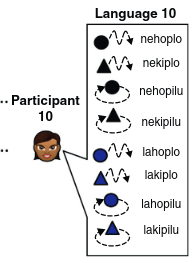

_________For example, Kirby et al. (2008) had participants assign nonsense-word labels to little shapes, with each person in the chain expanding the labels they were given to new little shapes. Over time, the mapping of labels to shapes began to exhibit compositional behavior. In their illustration, by the 10th person, each part of the made-up word has come to stand for a feature of the picture:

Tamariz, Mónica and Simon Kirby, “Culture: copying, compression, and conventionality,” Cognitive Science, 2015.

In this symposium, Sara Aronowitz discusses iterated learning as an experimental method and tool for simulation, with Thomas Icard providing commentary on its application to explanation.

Hilton, Denis, “Conversational processes and causal explanation,” Psychological Bulletin, 1990.

But the more ambitious the application of the method, the greater the gap between what’s happening in the experiment and what we want to model in the world. The Kirby et al. work is at the extreme end. A study in the lab has at most thousands of participants, each completing a task that takes minutes. The system it’s meant to be modeling in the world involves hundreds of years and millions of people. Most significantly, the interaction between participants in the lab is minimal and only in one direction. In real language development, interaction is (usually) cooperative and bi-directional.