A new biography, Places of Mind, by his student and friend Timothy Brennan, draws out many of the contradictions and puts them in personal and historical context.

Kenan Malik is an Observer columnist Arendt, Baldwin and Said were very different thinkers. What they had in common was a willingness to engage with the world and a fearlessness about standing on unpopular political principles. Engaging with a contradictory world inevitably leads one to grapple with contradictory views. There is a critical spirit in their work that makes their voices feel particularly vital today.

People such as Hannah Arendt, the German-born political theorist, who wrestled with conflicting views on democracy, human rights, the nation state and Marxism. Or James Baldwin, perhaps the most important chronicler of 1960s America, whose ambivalence about the role of the artist, the nature of protest and the meaning of identity was always on view.

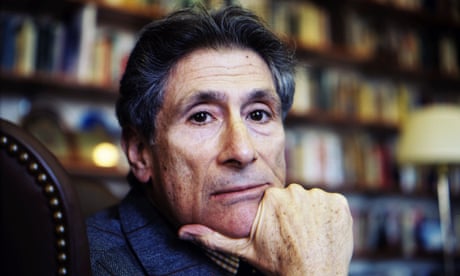

Then there’s Edward Said. In my first book, The Meaning of Race, published 25 years ago, I was critical of Said’s most celebrated work, Orientalism, which I argued was one-sided in its condemnation of the “western gaze”. Said unpicked the ways in which European thinkers created a mythical “Orient” but in doing so he manufactured a mythical idea of the west. That criticism holds, but I’ve since come to appreciate his eloquent humanism, his critique of the politics of identity, his support for the Palestinian struggle while never losing sight of the rights of Jews. Much of the postcolonial thinking and identitarian politics that Orientalism helped nurture, Said himself loathed.