Sandel’s politics are squarely on the left. In 2012, he added intellectual lustre to Ed Miliband’s renewal project for Labour, speaking to that year’s party conference on the moral limits of markets. The speech, and his book of the same year, What Money Can’t Buy, helped inspire Miliband’s critique of “predatory capitalism”, which was the Labour leader’s distinctive contribution to post-crash political debate in Britain.

But the main point of The Tyranny of Merit is a different one: Sandel is determined to aim a broadside squarely at a left-liberal consensus that has reigned for 30 years. Even a perfect meritocracy, he says, would be a bad thing. “The book tries to show that there is a dark side, a demoralising side to that,” he says. “The implication is that those who do not rise will have no one to blame but themselves.” Centre-left elites abandoned old class loyalties and took on a new role as moralising life-coaches, dedicated to helping working-class individuals shape up to a world in which they were on their own. “On globalisation,” says Sandel, “these parties said the choice was no longer between left and right, but between ‘open’ and ‘closed’. Open meant free flow of capital, goods and people across borders.” Not only was this state of affairs seen as irreversible, it was also presented as laudable. “To object in any way to that was to be closed-minded, prejudiced and hostile to cosmopolitan identities.” As he talks, the tone is as modulated as ever; the phrasing characteristically elegant and fluent. But a sense of frustration is palpable, as Sandel charts the rise of what he sees as a corrosive leftwing individualism: “The solution to problems of globalisation and inequality – and we heard this on both sides of the Atlantic – was that those who work hard and play by the rules should be able to rise as far as their effort and talents will take them. This is what I call in the book the ‘rhetoric of rising’. It became an article of faith, a seemingly uncontroversial trope. We will make a truly level playing field, it was said by the centre-left, so that everyone has an equal chance. And if we do, and so far as we do, then those who rise by dint of effort, talent, hard work will deserve their place, will have earned it.”

Fair competition does not constitute a just vision of society. Even if Trump is defeated in November’s presidential election, this is a truth, Sandel says, that Joe Biden, and his counterparts in Europe, must take on board. For inspiration, he says, they could do worse than turn to one of his intellectual heroes, the English Christian socialist RH Tawney.

What Money Can’t Buy sealed Sandel’s status as perhaps the most formidable critic of free-market orthodoxy in the English-speaking world. But as an age of violently polarised, partisan and poisonous politics has taken hold, it is that early encounter with Reagan that has begun to play on his mind. “It taught me a lot about the importance of the ability to listen attentively,” he says, “which matters as much as the rigours of the argument. It taught me about mutual respect and inclusion in the public square.”

The recommended way to “rise” has been to get a higher education. Or, as the Blair mantra had it: “Education, education, education.” Sandel homes in on a 2013 speech by Obama in which the president told students: “We live in a 21st-century global economy. And in a global economy jobs can go anywhere. Companies, they’re looking for the best-educated people wherever they live. If you don’t have a good education, then it’s going to be hard for you to find a job that pays the living wage.” For those willing to make the requisite effort, there was the promise that: “This country will always be a place where you can make it if you try.”

“Humility is a civic virtue essential to this moment,” he says, “because it’s a necessary antidote to the meritocratic hubris that has driven us apart.”

“Tawney argued that equality of opportunity was at best a partial ideal. His alternative was not an oppressive equality of results. It was a broad, democratic ‘equality of condition’ that enables citizens of all walks of life to hold their heads up high and to consider themselves participants in a common venture. My book comes out of that tradition.”

• The Tyranny of Merit is published by Penguin on 10 September (£20). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15

Donald Trump, who is a pernicious character. But my book conveys a sympathetic understanding of the people who voted for him. For all the thousands and thousands of lies Trump tells, the one authentic thing about him is his deep sense of insecurity and resentment against elites, which he thinks have looked down upon him throughout his life. That does provide a very important clue to his political appeal.

Michael Sandel was 18 years old when he received his first significant lesson in the art of politics. The future philosopher was president of the student body at Palisades high school, California, at a time when Ronald Reagan, then governor of the state, lived in the same town. Never short of confidence, in 1971 Sandel challenged him to a debate in front of 2,400 left-leaning teenagers. It was the height of the Vietnam war, which had radicalised a generation, and student campuses of any description were hostile territory for a conservative. Somewhat to Sandel’s surprise, Reagan took up the gauntlet that had been thrown down, arriving at the school in style in a black limousine. The subsequent encounter confounded the expectations of his youthful interlocutor.

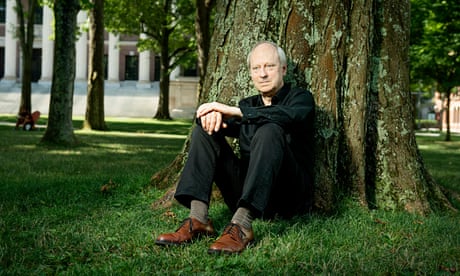

“I had prepared a long list of what I thought were very tough questions,” recalls Sandel, now 67, via video-link from his study in Boston. “On Vietnam, on the right of 18-year-olds to vote – which Reagan opposed – on the United Nations, on social security. I thought I would make short work of him in front of that audience. He responded genially, amiably and respectfully. After an hour I realised I had not prevailed in this debate, I had lost. He had won us over without persuading us with his arguments. Nine years later he would get elected to the White House in the same way.”

There must be a radical re-evaluation of how contributions to the common good are judged and rewarded. The money to be earned in the City or on Wall Street, for example, is out of all proportion with the contribution of speculative finance to the real economy. A financial transactions tax would allow funds to be channelled more equably. But for Sandel, the word “honour” is as important as the question of pay. There needs to be a redistribution of esteem as well as money, and more of it needs to go to the millions doing work that does not require a college degree.

“We need to rethink the role of universities as arbiters of opportunity,” he says, “which is something we have come to take for granted. Credentialism has become the last acceptable prejudice. It would be a serious mistake to leave the issue of investment in vocational training and apprenticeships to the right. Greater investment is important not only to support the ability of people without an advanced degree to make a living. The public recognition it conveys can help shift attitudes towards a better appreciation of the contribution to the common good made by people who haven’t been to university.”

“Am I tough on the Democrats? Yes, because it was their uncritical embrace of market assumptions and meritocracy that prepared the way for Trump. Even if Trump is defeated in the next election and is somehow extracted from the Oval Office, the Democratic party will not succeed unless it redefines its mission to be more attentive to legitimate grievances and resentment, to which progressive politics contributed during the era of globalisation.”

Henry Aaron, the black baseball player who grew up in the segregated south and broke Babe Ruth’s record for career home runs in 1974. Aaron’s biographer wrote that hitting a baseball “represented the first meritocracy in Henry’s life”. It’s the wrong lesson to draw, says Sandel. “The moral of Henry Aaron’s story is not that we should love meritocracy but that we should despise a system of racial injustice that can only be escaped by hitting home runs.”

So much for the diagnosis. The only way out of the crisis, Sandel believes, is to dismantle the meritocratic assumptions that have morally rubber-stamped a society of winners and losers. The Covid-19 pandemic, and in particular the new appreciation of the value of supposedly unskilled, low-paid work, offers a starting point for renewal. “This is a moment to begin a debate about the dignity of work; about the rewards of work both in terms of pay but also in terms of esteem. We now realise how deeply dependent we are, not just on doctors and nurses, but delivery workers, grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, lorry drivers, home healthcare providers and childcare workers, many of them in the gig economy. We call them key workers and yet these are oftentimes not the best paid or the most honoured workers.”

Sandel has two fundamental objections to this approach. First, and most obvious, the fabled “level playing field” remains a chimera. Although he says more and more of his own Harvard students are now convinced that their success is a result of their own effort, two-thirds of them come from the top fifth of the income scale. It is a pattern replicated across the Ivy League universities. The relationship between social class and SAT scores – which grade high school students ahead of college – is well attested. More generally, he notes, social mobility has been stalled for decades. “Americans born to poor parents tend to stay poor as adults.”

A new respect and status for the non-credentialed, he says, should be accompanied by a belated humility on the part of the winners in the supposedly meritocratic race. To those who, like many of his Harvard students, believe that they are simply the deserving recipients of their own success, Sandel offers the wisdom of Ecclesiastes: “I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding… but time and chance happeneth to them all.”