He told the Observer in 2020: “What we need is not only to modify the system of production but to get out of it altogether. We should remember that this idea of framing everything in terms of the economy is a new thing in human history. The pandemic has shown us the economy is a very narrow and limited way of organising life and deciding who is important and who is not important.

To put that into context, one of his most controversial assertions was the claim that Louis Pasteur did not just discover microbes, but collaborated with them. “If I could change one thing, it would be to get out of the system of production and instead build a political ecology.”

His large body of work ranged from philosophy and sociology to anthropology, and he had urged society to learn from the Covid pandemic, “a global catastrophe that has come not from the outside like a war or an earthquake, but from within”.

Latour dissected society’s different ways of understanding the climate emergency and communicating about it. In Face à Gaïa, a series of eight lectures published in 2015, he looked at how the separation between nature and culture enables climate denial.

Speaking to the LA Review of Books in 2018, Latour said: “Science needs a lot of support to exist and to be objective … [it needs] support by scientists, institutions, the academy, journals, peers, instruments, money – all of these real-world ecosystems, so to speak, necessary for producing objective facts.

Powers said: “With vigour, freshness, invention, honesty, expansiveness, art and playful humour, he is moving us out of our fantasies of control and mastery back into an embrace of evolving democracy.”

In February 2020 he staged Moving Earths, another blend of performance and lecture that showed “social and cosmic order lurching towards a parallel political and ecological collapse”.

In 2018, Latour said it was actually quite the opposite. “I think we were so happy to develop all this critique because we were so sure of the authority of science,” he told the New York Times.

Emmanuel Macron tweeted that as a thinker on ecology, modernity or religion, Latour was a humanist spirit who was recognised around the world before being recognised in France. The French president said Latour’s thoughts and writing would continue to inspire new connections to the world.

As well as his prominent work in academic spheres, including teaching posts at the École des Mines de Paris, Sciences Po Paris and the London School of Economics, Latour was also involved in the artistic world. He curated the exhibitions Iconoclash (2002) and Making Things Public (2005) at the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie in Karlsruhe, Germany.

He has also collaborated with the researcher and director Frédérique Aït-Touati on several theatre projects such as Gaia Global Circus in 2013 and the performance-cum-lecture Inside in 2017, using theatre to discuss everything from microbiology to democracy.

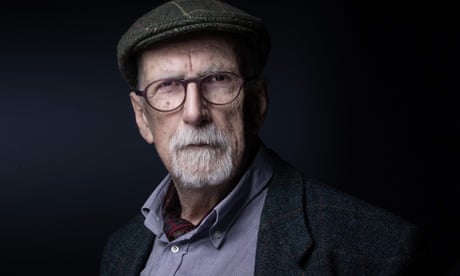

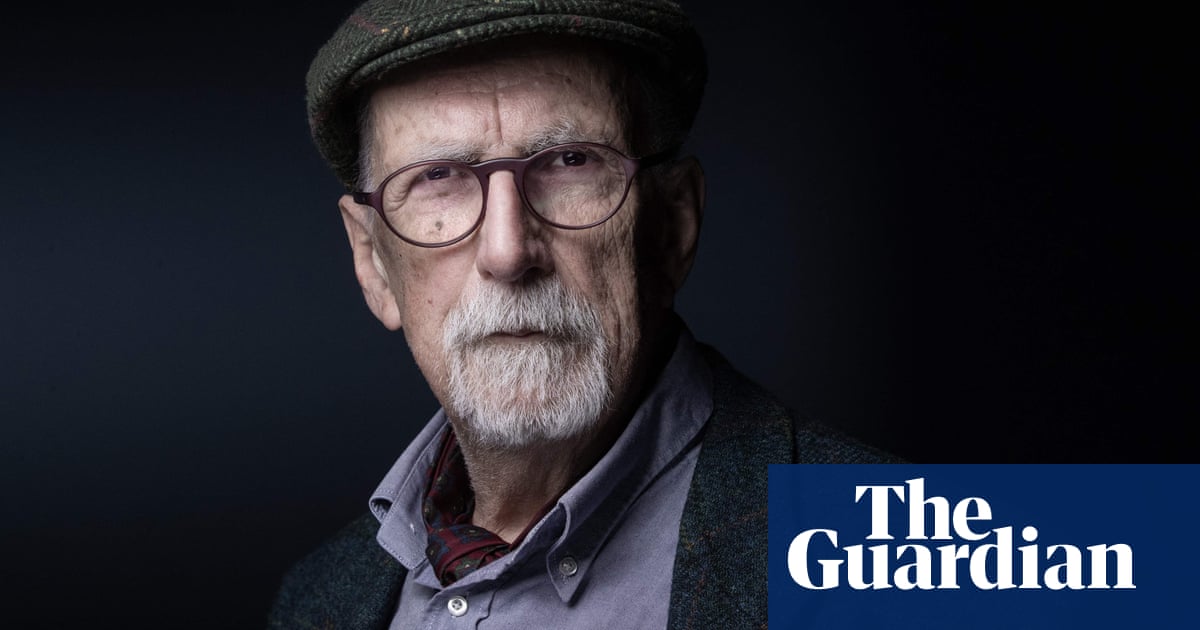

Born in 1947 into an established wine-making family in Burgundy, Latour attained a PhD in philosophy from the University of Tours, before turning his attention to anthropology, undertaking field studies in Ivory Coast and California.

Latour was considered one of France’s most influential and iconoclastic living philosophers, whose work on how humanity perceives the climate emergency won praise and attention around the world.

“Science depends on them just like you depend on the oxygen in this room. It’s very simple.”

The French thinker Bruno Latour, known for his influential research on the philosophy of science has died aged 75.

A pioneer of science and technology studies, Latour argued that facts generally came about through interactions between experts, and were therefore socially and technically constructed. While philosophers have historically recognised the separation of facts and values – the difference between knowledge and judgment, for example – Latour believed that this separation was wrong.

The physicist Alan Sokal was so enraged by the social constructionists’ approach he invited them to jump out the window of his flat, which was on the 21st floor. He was under the impression that they did not believe in the laws of physics.

The author Richard Powers has commented on the way Latour encouraged him to “think of all living systems – technological, social and biological – as interdependent, reciprocal and additive processes”.

He won the Holberg prize, known as the Nobel of the humanities, in 2013, hailed for a spirit that was “creative, imaginative, playful, humorous and – unpredictable”.

In the mid-1990s there were heated debates between “realists”, who believed that facts were completely objective, and “social constructionists”, like Latour, who argued that facts were the creations of scientists.

His groundbreaking books, Laboratory Life (1979), Science in Action (1987) and We Have Never Been Modern (1991) offered groundbreaking insights into, as he put it “both the history of humans’ involvement in the making of scientific facts and the sciences’ involvement in the making of human history”.