For several years Alison lay awake at night wishing her husband dead. Trapped in a miserable marriage, her preference was for a straightforward heart attack or massive stroke. But she also fantasised about a car crash or a fishbone getting stuck in his throat.

Nine percent of people thought they would live beyond their 90th birthday, and 8% thought they would die before reaching 65. The biggest group, a third, expected to die between the ages of 81 and 90. “The survey illustrates the misconception that the public doesn’t want to talk about death or dying. People really do – this is a topic people care about,” said John Troyer of the Centre for Death and Society at the University of Bath.

The finding is part of an extensive survey of attitudes to death carried out by YouGov and shared exclusively with the Guardian. It provides a fascinating insight into the range of views held by the public as taboos on talking about death continue to be broken down.

Almost half (49%) have pictured their own funeral, with 8% thinking about it in detail. Cremation is the preferred option for 45%, with only 15% saying they want to be buried and one in eight (13%) saying they would like to donate their body to research.

Alison’s thoughts may sound extreme but she is among a third of Britons who have seriously wished death upon someone, according to new data. More men than women have harboured such thoughts, and three-quarters said they had no regrets. People were not asked why they wished someone dead.

Three-quarters said they would be prepared to die to save someone’s life. For one in 10, there is no one for whom they would sacrifice their life.

According to the poll, almost three-quarters of Britons say they are comfortable talking about their own death – with over-40s markedly more at ease than younger people. This reflects a cultural shift towards greater openness about terminal illness and grief in recent decades, and an increase in support organisations helping people come to terms with impending death and planning their own funerals.

According to the poll, almost one in 10 Britons think about death – their own or in general – every day, with another 20% thinking about it several times a week. Only 4% say they never think about it. Two-thirds say there are worse things than death, citing living in pain, having a serious incapacitating illness, being tortured, or losing a loved one, particularly a child.

YouGov questioned 2,164 UK adults earlier this year

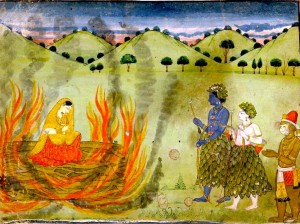

A third of Britons believe in an afterlife. Among those, the biggest group (43%) think a soul goes to heaven or lives on in some way, 16% believe in reincarnation, and 6% think they will become a spirit. A majority of those questioned (54%) do not believe in heaven or hell, but 10% of non-religious people believe in both.

People taking part in the survey were fairly evenly split over fear of dying: 41% said they were afraid, with 43% saying they were not. Young women were most likely to be fearful, and men over 60 least afraid. People who practise a religion were less likely to be fearful than non-religious people – but not by much: 51% compared with 42%.

Surprisingly, the Covid pandemic, which by the end of last month had claimed almost 160,000 lives in the UK, has had no impact on a large majority (69%) of people’s perception of death. Among the one in four people who said it had affected the way they viewed death, most had become more worried about losing someone close to them.

Pop-up “death cafes” have emerged in dozens of countries, drawing in thousands of people to discuss death. Television programmes and books have embraced the issue, sometimes with humour. Debates on assisted dying have raised issues around end-of-life care. Some have suggested that the boomer generation, facing its own mortality, is freeing death from the shackles of taboo in the same way it championed sexual liberation in the 1960s.

“I thought death would be a good outcome,” she said. “I’d be free, yet everyone would feel sorry for me.” Eventually the couple went through an acrimonious divorce, but both remain in good health.

More than half (56%) said it was acceptable to celebrate or rejoice at someone’s death, with young men significantly more likely to think cheering someone’s demise is OK than any other group. Almost one in four people said someone’s death could never be a cause of celebration.