[3] Please don’t guess Flamengo; the right answer is Fluminense.

These three types of preference provide some structure, though they will typically be localized. They might generate fine-grained preference orderings among possible means of building a house, but they will say very little about choosing among competing ends for which we have not formed reflective preferences, or at least not reflective preferences that are fine-grained enough. But this is not necessarily an area where decision theory excels; this is the terrain of “incomparability” and “incommensurability” where the tools provided by decision theory break down. The main problem so far is that it is not yet clear how this limited ordering will help us understand the nature of rational agency under risk. In order to do this, ETR needs a bit more equipment.

You have arrived at the realization that your two ends are incompatible, at least in their unrestricted version: you cannot have both the ends of singing as much as possible, and being as good a marathon runner as possible. Since it is, according to the Extended Theory of Rationality (ETR), incoherent to pursue incompatible ends, you must give up or modify at least one of them. You could give up singing altogether or marathon running altogether, or you could have as an end to sing a lot and be a decent marathon runner, or to be a committed marathon runner and sing from time to time. ETR is completely neutral on the question of how you should revise these ends; it only says that you must revise them. So far, this seems right to me; in fact, I argue that attempts to say that it matters how strongly you desire each of these things will quickly collapse into a form of normative hedonism. But hedonism is not a theory of instrumental rationality; it is a substantive view about intrinsic value. However, in some cases, comparisons are important for the theory of rationality, and it seems undeniable that sometimes what I prefer is relevant to my rational agency. Moreover, comparative attitudes seem particularly important in contexts in which I face risk or uncertainty: how can we evaluate prospects with radically different outcomes if we can’t compare the value of these outcomes? On one side, we have ETR embarrassingly silent; on the other side, we have decision theory flaunting its impressive mathematical prowess. There seems to be no contest.

Three Types of Preference

Preference Relative to an End

Well, if you can’t beat your enemy, join them, or at least steal their stuff. I argue that ETR can piggyback on decision theory at exactly the choice contexts in which decision theory is at its most plausible. And it can part ways with decision theory, when decision theory starts becoming implausible. How is that for snatching victory from the jaws of defeat? In order to make good on these promises,[1] let me explain how ETR generates comparative attitudes such as preferences.

Pareto Preferences

You start your adult life having only one end; namely, singing. Your whole life is dedicated to it. But then, one day you discover the joys of marathon running, and now you have two ends: singing and running marathons. As you go out for your first training run, you realize that as you huff and puff, your singing suffers. You stop to hit the right note, but then you realize that you’re no longer training as you should.

Reflective Preferences

The End of Happiness and General Means

Here are two ends I am constantly pursuing: the end of following my Brazilian team[3] and the ensuring the welfare of my children. Here I am in the middle of Fluminense’s game at a tense moment, when I notice that my child is in distress and needs my immediate attention. There is no question in my mind which end I need to pursue; I must keep watching tend to my child’s needs. This is not because my desire for the welfare of my children is in some way stronger at that moment, but because I have a higher-order end that I am also pursuing; roughly, the end of giving priority to the pursuit of my child’s welfare over the pursuit of my end of supporting my team.

Most of the ends we pursue have a certain internal structure. So if my end is to build a house, there will be better and worse houses, and thus better and worse realizations of the end. Although I will have realized my end if I build an acceptable house, in pursuing this end I am guided by its internal structure. If no other ends are even implicated, then a rational agent pursuing the end of building a house who faces the question of whether to build it from sticks, straw, or bricks, will not be in a Buridan’s ass situation: the nature of the end determines that they use bricks, even if a straw house is an acceptable one.[2]

Risk

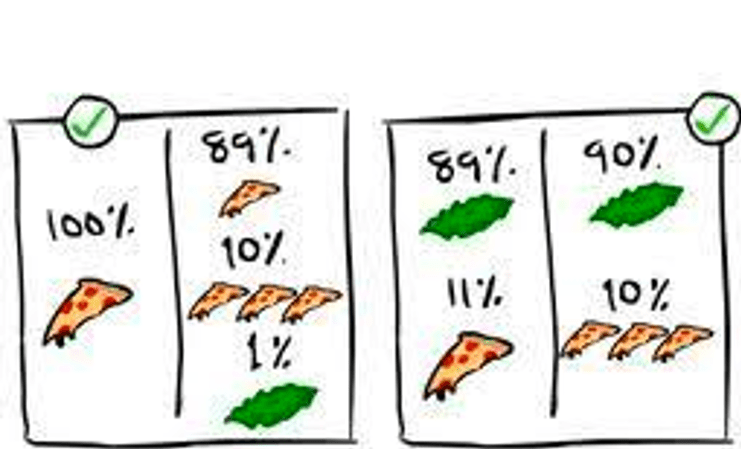

This strategy has its limits. Let us take, for instance, the Allais paradox. One of the options in the Allais paradox is making a million dollars. This choice is often represented as “100% chance” of getting a million dollars, but I argue this is wrong; this option is better represented as a case of knowledge that you will make a million dollars. This makes this option essentially different from the others, and turns it into an option that cannot be governed by our end of (merely) trying to make money. So ETR cannot rule out that a rational agent will choose to make a million dollars even if their reflective preferences (their risk function) would otherwise determine that they choose the “risky” option. But this is a welcome consequence; this is how most of us are inclined to choose, and it seems perfectly rational.

[4] Or at least preparing to travel to Rio de Janeiro; in the book, I argue that for our purposes, it is not relevant when the proper action of travelling to Rio de Janeiro begin.

Given our awesome reflective powers, we can think of the ends that we are pursuing as a totality, and engage in their coordinated pursuit. This is what I call, “the end of happiness”, the end of pursuing all our ends well. There are certain means to this end, means that we pursue not for the sake of specific ends but as means to whatever we might be pursuing. So if I decide to follow my doctor’s advice that I should cut down my espresso consumption to 10 cups a day, I might not be doing so for the sake of any particular end, but as a way of better (or at least less jitterily) pursuing many, or all, of my ends.

[1] Of course, here I can only give a sketch of the argument. For the full spectacle, you’ll need to buy the book!

[5] Or kind of new.

[2] My explanation of why the end has this structure is based on my views that all our actions are done under the guise of the good; the structure is inherited from the nature of the good you are pursuing. But ETR is not committed to this explanation.

In the book, I argue that ETR is also more promising in dealing with purported cases of bias such as the endowment effect or mental accounting. But I can’t give it all for free; you need to buy the book for these goodies. Meanwhile, don’t be too disappointed! Tomorrow’s free sample will bring you something completely new[5] and revolutionary:[6] the idea of an instrumental virtue.

Last week, I started engaging in (what seemed to me at the time) the temporally extended action of travelling to Rio de Janeiro.[4] After calling a few airlines and looking into COVID travel restrictions, it became increasingly clear to me that I did not know whether it was possible to fly to Rio from Toronto and back in the dates available to me. As soon as I realize that I do not know that it is actually possible for me to travel, the action of travelling to Rio is no longer a possible action for me. Contemporary theories of rationality often treat decision under risk as a function of the value of certain choices under certainty or knowledge. In decision theory, I weigh the utility of each possible outcome by the probability that it will obtain in order to determine the utility of an act. But under ETR, my state of knowledge changes the range of actions open to me. I can no longer be engaged in travelling to Rio, even if I can be engaged in various related pursuits: improving my chances of going to Rio; pursuing opportunities to go to Rio; leaving open the possibility of being in Rio next month; and so forth. ETR does not imply that a rational agent will now engage in any of these related actions. Again, this seems the right result; instrumental rationality should not require any specific revisions to my end when I realize it is not in my power to ensure that I will be in Rio in the near future. However, an option that I do have is to make a rather minimal revision in my end, and pursue instead the end of trying to travel to Rio. Just like the end of building a house, trying has an internal structure: I am arguably not even trying to dance the tango if I just move my right foot distractedly to the side a couple of times; I am doing better if I attentively follow these instructions, and possibly even better if I brush up on my Spanish and watch this video. I argue that the internal structure of trying gives rise to very basic risk principles, such as, for instance, that, ceteris paribus, a rational agent trying to X faced with a choice between two ways of trying to X will choose the one that is more likely in resulting in their X-ing. Such basic principles are obviously a far cry from the powerful principles of decision theory. But let us take our end of making (enough) money. In various circumstances, an obvious means to this end is trying to make money. The end of trying to make money will inherit its internal structure from the end of making money, but it doesn’t determine a particular way of balancing, for instances risky attempts of greater gains and safer bets at lower ones; for this we need reflective preferences in which agents can give different kinds of priority to one over the others. Risk functions of classic decision express possible forms of these reflective preferences. More liberal approaches to incorporating risk, like Lara Buchak’s risk-weighted expected utility model, provide us with a wider menu of reflective preferences; I argue in the book that ETR will likely allow attitudes to risk even more permissive than the ones allowed by Buchak’s theory. But the important point is that, under ETR, these risk attitudes are ways of making more determinate the internal structure of the indeterminate end of trying to make money.