• In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.

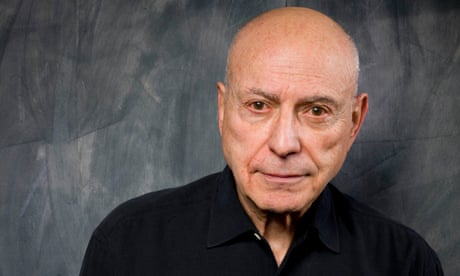

Alan Arkin met his guru on a Hollywood film set in 1969. Arkin was the star and John was his stand-in, a lowly factotum, the id to his ego. At the time, Arkin was successful but unsatisfied, looking for meaning, craving some guidance. His encounter with John set him on a path towards enlightenment that continues to this day. As for the guru, he took a different, darker route.

Maybe it’s all dirty. Maybe chuck it all out. “Well no,” he says. “Because I was finally able to sort it out. I felt that I had grown so much. So much had borne fruit. Some miraculous things were going on as a direct result of meditation. It saved my life. I couldn’t throw it out. If I threw it out, then suicide would have been the only viable alternative. And for reasons which we’ll go into over a cup of tea one day, I knew that suicide was not the answer. I knew that suicide was not going to solve anything for me or my family or anybody I knew.”

Arkin recently wrote a book, Out of My Mind, about his spiritual journey and the lessons he’s learned. He subheaded it “Not Quite a Memoir” because he worried that people might be expecting a tell-all autobiography, the sort of gossipy trash he’d never write. Damned if he’s going to dish the dirt on Audrey Hepburn, Al Pacino, Johnny Depp and all the others he’s worked with. He’d rather write about meditation, reincarnation and Tibetan Buddhism. He’d rather write about John – at least up to a point.

I tell him that it sounds as though he’s preparing for the end. But that’s a crass western notion. It risks missing the point of his book. “There is no end,” Arkin says. “There was no beginning and there is no end. We are all a part of that endless flow.”

reportedly put in a trance-like state and then molested. The tabloid press dubbed him The Creep Guru.

He’s happier now, thanks to his meeting with John and the changes it brought. In his book he writes (always charmingly; sometimes convincingly) about past lives and faith healers and the tenets of eastern philosophy. He tells us about John, who he worked with for over 20 years and who became a central figure in his life. John led the way, Arkin gratefully followed. He writes: “My devotion to his teachings became virtually ironclad.”

I ask Arkin if I have this right – if his John was that John – and he sighs. “Oh my God, that was a dark night of the soul if ever there was one. I can’t even begin to tell you what that meant, not just for me but for my family. I could hardly leave my room for about six months. I found myself saying, ‘Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater.’ But I couldn’t work out what was the baby and what was the bathwater.”

I can’t help feeling that Out of My Mind would have been a richer, darker book if it had focused more on the shifting relationship between the actor and his stand-in, the star and his shadow. But Arkin is determined to accentuate the positive. It’s part of his philosophy, the path that he’s chosen. The world is full of such storm-clouds, it’s best to limit your exposure. He explains that he and his wife lead a quiet life in California now. They rarely leave the house and avoid discussing politics, or the state of the environment. “I don’t want to live in a state of terror,” he says.

I’ve read that Battista killed himself. “He did, yeah, that’s true,” Arkin says. “But I doggedly went on and I’m glad that I did.”

“I had this sense that I didn’t exist. My parents were wonderful people in many ways, but they weren’t affectionate. I don’t remember ever being touched by either one. I felt ignored to the point where I didn’t even exist – so acting was my lifeline to not feeling like I was being obliterated. For many years, the only place I felt alive was on stage.”

The older he gets, he says, the more he has come to appreciate silence and solitude. “Beethoven used to be a heroin injection for me. Jazz, the same. The great novels, the same. I could not conceive of going through a day without reading great literature or listening to great music. Now it’s mostly an assault. Living in silence. Looking at the garden. Having a relationship with trees and flowers and the sky. That’s what’s profound to me now.”

• Out of My Mind by Alan Arkin is published by Viva Editions.