I lack space to discuss all of these concerns, but want to remark very briefly on two of the most important.

Laplane, L., Mantovani, P., Adolphs, R., Chang, H., Mantovani, A., McFall-Ngai, M., Rovelli, C., Sober, E., & Pradeu, T. (2019). Why science needs philosophy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(10), 3948–3952.

This textbook presentation of what our phenomenology is like not only seems to ignore a large philosophical debate, but it also reveals a gap between the questions psychologists seem most interested in asking (e.g. about the mechanisms of shape constancy) and the philosophical questions about what objects look to us.

Philosophy of Perception in the Laboratory

Jorge Morales

_________

This textbook presentation of what our phenomenology is like not only seems to ignore a large philosophical debate, but it also reveals a gap between the questions psychologists seem most interested in asking (e.g. about the mechanisms of shape constancy) and the philosophical questions about what objects look to us.

Commentary: On the Representation of Proximal Shape

Jonathan Cohen

_________

There is no doubt that the philosophy of mind has benefited immensely from considering findings from the empirical literature. Rather than trying to introspect what experiences are like, psychological evidence can be leveraged to populate premises with empirical content in philosophical arguments. Merely using available empirical findings, however, has an important limitation: its passive nature. All philosophers can do is hope that the questions they are interested in have been previously addressed. Psychology is a rich field, and there is a lot of relevant research that philosophers can use. However, at least in my experience with consciousness and perception research, it is often the case that there is only neighboring work relevant to the questions we philosophers ask. This might be in part because of the difficulty of studying subjectivity and phenomenology in the laboratory. But there are sociohistorical reasons too. Like any other field, psychology is often concerned with questions that stem from within psychology itself. This is not necessarily because psychologists do not care about philosophical questions about perception (some would, if they knew about them), but because research is to a large extent framework-dependent: some questions only come up while working within a particular tradition or theoretical framework. This entails that particular empirical questions that are important to philosophical debates about conscious experiences may not come up in psychology hallways at all. When this happens, both fields lose. Philosophers are limited to extrapolating results from nearby debates because their (empirical) questions are not being addressed, and psychologists miss the opportunity to test new hypotheses that are often part of a long and theoretically rich tradition. The value of philosophy for science is often laid out in terms of philosophy’s theoretical contributions when reflecting about science (Laplane et al., 2019; Thagard, 2009), but it can also feed questions directly into scientific research programs.

- ellipticality exclusively (Locke, 1975, II, ix, 8);

- roundness exclusively (Smith 2002, Schwitzgebel 2006, Hopp 2013); and

- both ellipticality and circularity (Peacocke 1983, Noë 2004, Schellenberg 2008, Cohen 2010, 2012).

In this symposium, Jorge Morales makes the case for philosophers of perception conducting experiments of their own, with Jonathan Cohen providing commentary on Morales’ empirical work on perspectival shape.

Morales reports a set of experiments (Morales, Bax, & Firestone, 2020) bearing on this issue. The headline finding here is that visual search for a target oval shape seen head on was impaired by the presence of circular objects rotated in the depth dimension (relative to visual search for ovals seen head on in the presence of circles seen head on). That is (adopting Morales’s terminology), visual search for a target was impaired by the presence of distractors that shared a proximal (/perspectival) shape property, even when target and distractors differed (and participants successfully judged that they differed) in distal shape.

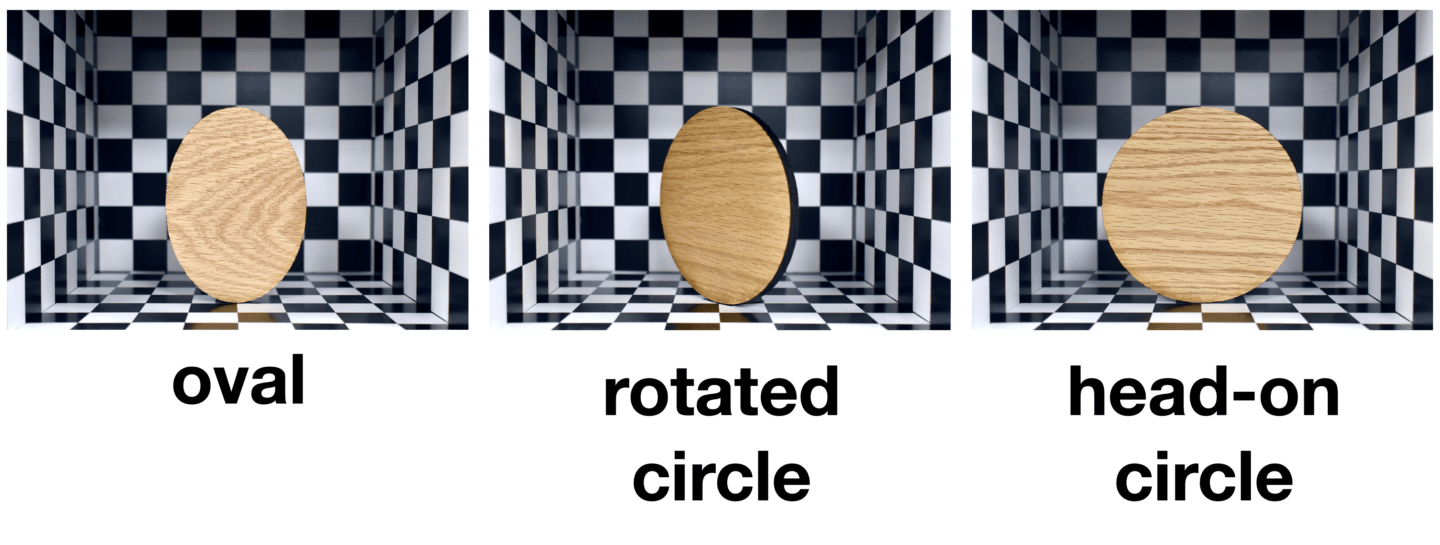

What about vision scientists? Naturally, they investigate the mechanisms and computations responsible for transforming the retinal images with which visual processing begins into the full-blown 3D representations that characterize our visual perception. In fact, one of the most foundational principles in all vision science is that vision goes beyond the retinal image. This view, popular from Helmholtz and Marr to textbooks, assumes that “perhaps the most fundamental and important fact about our conscious experience of object properties is that they are more closely correlated with the intrinsic properties of the distal stimulus (objects in the environment) than they are with the properties of the proximal stimulus (the image on the retina). This is perhaps so obvious that it is easily overlooked.” (Palmer, 1999, p. 312)

Philosophers have arrived at these incompatible positions mostly by resorting to introspection (which sometimes can be reliable (Morales, Forthcoming), but not always), and in some recent cases, by relying on available empirical evidence too. Some—recognizing the importance of designing experiments that directly address philosophical questions—have even suggested possible studies that would help make progress in our understanding of perspectival shapes (Schwenkler & Weksler, 2019). However, philosophers have not really been involved in empirical research that tackle this kind of problems in the philosophy of perception head on.

Hopp, W. (2013). No Such Look: Problems with the Dual Content Theory, Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 12(4), 813–833.

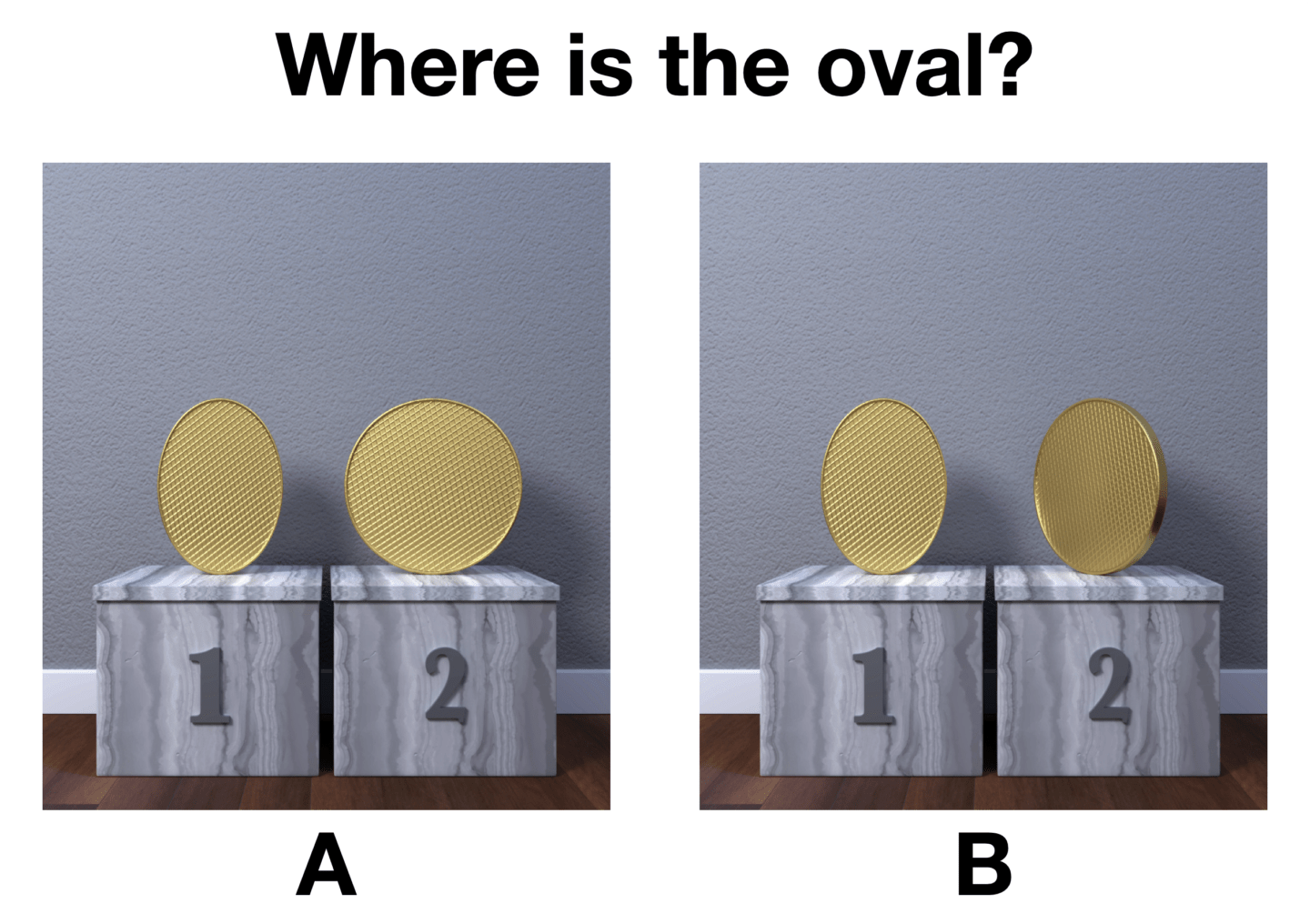

Look at the golden “coin” in the image below. What shape do you see?

Schwenkler, J., & Weksler, A. (2019). Are perspectival shapes seen or imagined? An experimental approach. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 18, 855-877.

Consider this philosophical chestnut: when you look at a tilted dinner plate, what shape do you see? Answers offered in the literature to this or nearby neighboring questions include:

The results from our experiments suggest that subjects do experience both the true distal shape of objects and their subjective, perspectival shapes. Recall that subjects barely made mistakes selecting the oval, which indicates that mechanisms of shape constancy were effective and allowed subjects to clearly distinguish between true ovals and rotated circles. The reaction time slowdown that we observed over and over again strongly suggests that, despite some philosophical intuitions and cognitive science’s assumptions, our conscious experiences continue to represent perspectival properties even after our visual system resolves the true shape of objects.

To overcome these limitations, philosophers of mind (and psychologists!) can embrace the strategy of designing and running philosophy-specific experiments themselves. We see this trend in Experimental Philosophy, where philosophers test people’s intuitions about different concepts in moral psychology, epistemology, and language. In psychology and neuroscience, we see significant philosophical influence in areas concerned with morality, modality, memory, imagination, and the neural correlates of consciousness. Surprisingly, however, this kind of direct involvement from philosophers in empirical research has been very limited when concerned with questions about perception. To emphasize, this is not to say that there are not lots of empirical research programs relevant to the philosophy of perception, or that some psychologists have found some inspiration in philosophical work. What seems to be lacking is an explicit effort to address problems that stem from the philosophy of perception with the full toolkit of experimental psychology.

Peacocke, C. (1983). Sense And Content: Experience, Thought, And Their Relations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

References

_________

Arend, L., & Reeves, A. (1986). Simultaneous color constancy. Journal of the Optical Society of America, A, Optics, Image & Science, 3(10), 1743–1751.

Thagard, P. (2009). Why Cognitive Science Needs Philosophy and Vice Versa. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(2), 237–254.

Second, while Morales et. al.’s experiments give us reason for believing that proximal shape is psychologically represented, distance remains between the latter conclusion and related but distinct claims that philosophical dispute has often centered on–e.g., that proximal shape is represented perceptually rather than post-perceptually, that it is a property we see rather than make inferences about, that it is represented at a personal rather than subpersonal level, or that it figures in the phenomenal character of our experiences.

Rose, D., & Danks, D. (2013). In defense of a broad conception of experimental philosophy. Metaphilosophy, 44(4), 512–532.

Subjects were indeed slower selecting the oval coin when it was next to a rotated circular coin (and hence shared the oval target’s perspectival shape) than when the exact same circular object was seen head on. It is important to note that subjects were very accurate, so they were not slower because they misperceived the shapes. To make sure this result could not be explained by some alternative factor, in eight subsequent experiments we controlled for all sorts of confounds, and every single time we found the same kind of interference. For example, we controlled for low level properties such as size and rotation; we also used moving objects that provided extra visual cues about the shapes of the objects, and we allotted extra time for viewing the stimuli ensuring subjects had all the depth cues they needed to process the shapes correctly and efficiently. We also showed that the effect generalized to other shapes such as trapezoids & squares. Importantly, we found the same effects when we used real 3D objects rather than computer-generated stimuli. After all, the realistic-looking computer-generated images like the ones above only fake 3D properties through clever computer algorithms; in the end, they are flat 2D images presented on a screen. But when selecting a laser-cut 3D oval object like the one below, subjects were slower when the distractor was a rotated circular “coin” than when the distractor was a circular “coin” seen head on. And all this in the real world with real objects!

Many arguments in the philosophy of mind hinge on capturing what experiences are like and what they are about. Philosophers’ main method to learn about the nature and contents of mental states has been to introspect them. Our capacity to introspect, however, is often unreliable. To avoid the muddy waters of introspection, philosophers of mind can take two (mutually non-exclusive) approaches to support the empirical claims in their arguments. After all, introspective reports are meant to reveal empirical truths about the mind. The first strategy is to get acquainted with the empirical literature with the goal of finding evidence that is relevant for their philosophical arguments. The second strategy is to run experiments meant to produce the desired evidence (Rose & Danks, 2013). In my research, I have followed both approaches, but here I will argue in favor of directly running philosophy-inspired experiments that take advantage of the full set of methods that psychological research has to offer. In particular, I will focus on testing questions in the philosophy of perception.

2. A similar point applies to the question about whether proximal shape figures in our phenomenal experience. Morales suggests this is indeed part of his quarry in characterizing his aim as “capturing what experiences are like” (p1). However, once again, though the results offered give us powerful reasons for believing that proximal shape is represented somewhere in our psychologies, they are not by themselves capable of settling whether such representations are accessible to consciousness. This seems important, because philosophers and psychologists who have defended positions like (ii) above (cf. Thouless 1931 on the “phenomenal regression to the real object”) are reasonably read as repudiating proximal shape qua accessible feature of phenomenal experience, rather than qua feature represented within our psychological makeup full stop.

(For an analogous demonstration with respect to color perception–viz., that there is an aspect of perceptual performance predicted/explained by representations of proximal rather than distal color, see Arend & Reeves, 1986, and the experimental literature stemming therefrom. As in the case of Morales et. al.’s experiments on shape perception, it’s hard to see how to make sense of these findings without accepting representations of the relevant proximal properties.)

Locke, J. (1975). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (P. H. Nidditch, Ed.). Clarendon Press.

First, if the reported increase in reaction time on visual search for targets matching distractors in proximal shape gives us reason for believing that proximal shape is (/other proximal properties are) psychologically represented, this finding alone says nothing about whether there are, additionally, representations of distal shape (/other distal properties). Now, in the present case, the further observation that participants successfully judged whether targets and distractors matched in distal shape suggests that they are indeed representing distal shape as well. The crucial point, however, is that the evidence for the reality of proximal representation, considered by itself, is agnostic on the distinct question of the reality of distal representation.

This is an important result. That said, it leaves some issues unresolved as well. (This is only a clarification; I don’t mean to suggest that Morales thinks otherwise.)

In sum, Morales et. al.’s result strikes me as a significant contribution to our understanding of the psychology of shape perception, though one that invites further inquiry (and funding). As supporters of the cause of full employment for cognitive scientists, surely this is something we can all applaud.

Welcome to the Brains Blog’s Symposium series on the Cognitive Science of Philosophy! The aim of the series is to examine the use of methods from the cognitive sciences to generate philosophical insight. Each symposium is comprised of two parts. In the target post, a practitioner describes their use of the method under discussion and explains why they find it philosophically fruitful. A commentator then responds to the target post and discusses the strengths and limitations of the method.

Palmer, S. E. (1999). Vision Science. MIT Press.